A dream is thinking that persists in the state of sleep. – Aristotle

INTRODUCTION

The Interpretation of Dreams is nearly a 700-page book, and roughly the first fifth comprises a ‘summary’ of Freud’s incredibly extensive research on dreams, dating from ancient Greece to his contemporaries in the 19th century. It is out of the scope of this text to recapitulate his effort, but it’s safe to say that very few people delved into this topic as Freud did. His views on the meaning of dreams and dream interpretation are arguably the most comprehensive done by any researcher in human history. Backed by his clinical practice, he formulated a breakthrough thesis that dreams fulfill infantile wishes, and that sexuality played a big part in driving them. Though only skimmed over in this book, his perspective on the role of sexuality in early life would be as central to the success of the treatment as controversial for the medical field at the time.

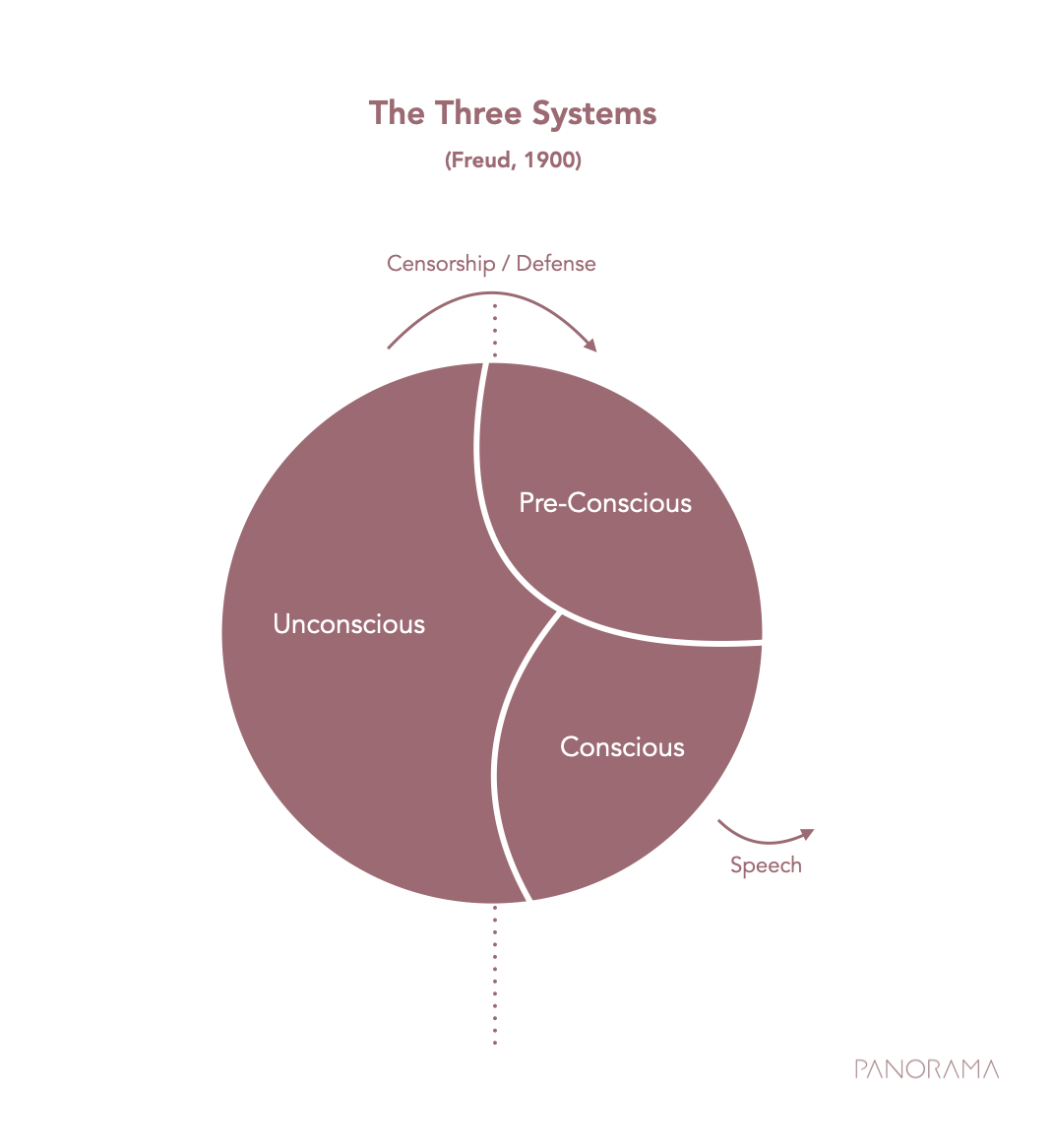

In laying out his thesis, Freud made use of two other invaluable overarching concepts: the first, a schematic presentation of the human psyche, split into three systems – the conscious, the pre-conscious, and the unconscious – which would support Freud’s understanding of where dreams would form and why we tend to forget or discard them. The second is the application of Greek mythology to make sense of complex concepts, referencing the myth of Oedipus Rex for the first time. The former was only representative of Freud’s First Topic, comprising his work until 1923, whereas the latter would not only support his work until his passing in 1939 but evolve into a paradigm for Psychoanalysis – a way of seeing and solving problems.

ORIGINS OF DREAMS AND DREAM-WORK

Freud’s curiosity about dreams is already noticeable when he alludes to them in Studies of Hysteria. There, he and Josef Breuer describe the phenomena of hysterical breaks as capable of producing a self-hypnotic, dream-like state where patients often hallucinated or presented momentary speech disorders that resembled what goes on during a dream. The hysterical phenomena revealed new parts of the psyche, opening the door for Freud’s initial formulations of the unconscious. Unlike his predecessors, who generally saw dreams as whole-pictures and assigned them nonsensical or worthless meaning, Freud instead (and again, much like how he re-signified hysterical symptoms years earlier) saw in dreams the access to the unconscious: puzzles comprised of symbolic relations, carriers of codes and messages that needed to be deciphered through interpretation, that quickly became pivotal in the work of analysis and mitigation of symptoms.

STIMULI AND MATERIAL FOR DREAMS

Several researchers before Freud or contemporary of his had already figured out that dreams could be induced, both via external stimuli (e.g., warming up a room could lead to dreams of fire) and internal/somatic stimuli (e.g., a dreamer bothered by leg pain could have a dream about it). For Freud, the intriguing was dream-content that did not subscribe to these types of stimuli but rather to psychical excitation – mind driven – and here is where he rested the focus of his research and formulation of his theory after that.

He initially discovers an intrinsic connection between the dream and the waking life, where the former borrows from the latter. Patients would dream about recent scenes or indifferent episodes that occurred the day before the dream, for which Freud gave the name of day's residues. Interestingly, daily residues blended with other remembrances that derived from much more ancient memories or experiences lived by the dreamer, even capable of tracing as far as childhood. Freud later postulated that these old memories had a more substantial charge influencing the buildup of a dream because their driving force was a repressed affect associated with a memory (much similar to the process of erupting hysterical symptoms). Day's residues, although vivid, played a secondary role in complementing the dream.

Freud also discovered that dreams select their material according to a rather peculiar logic of order and relevance that the dreamer would regard as absurd or illogical. Dreams can access the infancy of the dreamer and recover forgotten details, and infantile scenes manifest in dreams are only represented by an allusion that needs to be developed through interpretation. The deeper the analysis of the dream, the more the dreamer would encounter their childhood experiences.

Along with such discoveries came obstacles Freud needed to overcome, precisely the fact that most people forget their dreams after they wake up. He figured out that this happened firstly because people generally render the content of their dreams illogical, therefore giving them little or no attention and allowing it to slip through the day. Secondly and more importantly, whenever people are troubled by the content of a dream, they prefer to set it aside intentionally. Still, its content is also repressed by their consciousness involuntarily. Here is where Freud became even more intrigued because he realized a defense mechanism, a resistance, to repress material associated with something traumatic, which in turn caused the birth of symptoms.

FUNCTION OF DREAMS AND DREAM-WORK

Apart from a standard view in medical circles around the late 19th century that considered dreams a mere continuation of waking life psychical activity, thus serving no function, Freud argued that dreams revealed something else about the human mind instead. His thesis was that during sleep, the psychical activity loosens, and the psyche, freed from reason, has exceptional capacities and acts generatively and symbolically.

By analyzing children’s dreams, Freud concludes that the fundamental purpose of dreams is to answer a wish. He initially called them “comfort dreams.” In analyzing infant relatives, including his daughter, Anna Freud, he has the insight when she recalls a dream where she was eating strawberries, which took place after the family had spent the day before hiking along strawberry fields, and her parents had denied her strawberries. Freud tested this hypothesis exhaustively and learned that, while the connection between a wish and dream-content was very explicit in children, in adults, however, it wasn’t as evident due to a much more elaborate psychical activity capable of producing resistance. Wishes were disguised.

The poet's lack of creativity comes from the coercion that reason exerts on imagination. - Freud

The distortion to cover up the wish is what Freud defined as dream-work, the very resistance against an unbearable affect associated with the wish. Distortion occurs to shield the conscious system from a repressed idea or representation in the unconscious. Satisfying a repressed wish that incites pleasure but is perceived as displeasure by the conscious system produces anxiety, a symptom of fulfilling an unconscious wish. In adults, the wish is never straightforward; it needs to be accessed via interpretation, and often dreams have varied meanings, fulfilling several wishes in one dream; one wish can cover another until eventually arriving at a childhood wish.

The fulfillment of a wish isn’t expressed through analyzing the manifest content (the one dream remembers) present in the conscious system but through latent content in the unconscious. Censorship enacted by the pre-conscious system causes the dream to warp, and the greater it is, the greater the disguise shown in the dream. Freud discovered that censorship could invert an affect entirely, and he saw the turning of latent into manifest content as a psychic act.

Freud discovered that some dreams could also counter a wish when he noticed that patients resisted the analysis, wishing the analyst was wrong. In other instances, wishes would seem illogical, such as when the patient dreamt of punishing themself for something they judge they did wrong.

CONDENSATION AND DISPLACEMENT

One of the main characteristics of dream-work is mixing different ideas or representations in one, in a process Freud defined as condensation. An example is the production of a mixed dream person that combines characteristics of different people the dreamer knows. The mixed dream person shows up in the manifest content, and through interpretation, the dreamer can bring forth what or who constituted that character in the latent content. Condensation of images ultimately produces approximations, working as a middle ground, admitting multiple interpretations, and leading to different groups of ideas/representations.

Dreams don’t distinguish between wish and reality. In dreams, even if the ideas/representations are imaginary, their affects are real. In waking life, an affect only exists in tandem with an idea. However, in the dream, not all ideas carry the same affect one would expect in waking life. The work of displacement replaces a charged representation with something less relevant while the affect remains unchanged, causing a mismatch between representation and affect. Displacement takes the focus away from the main content of latent content, producing the distortion of the unconscious wish of the dream – an endopsychic defense.

People are reluctant to take responsibility for the immorality of their dreams. – Freud

Both processes funnel latent content from the unconscious system into manifest content that the dreamer remembers – the very process of disguising the wish. Think of it as repressed material that, in attempting to reach consciousness, can only do so by succumbing to its laws, expressed in coded ways more digestible by the conscious system. Thoughts in waking life happen through concepts, whereas in dreams, involuntary images prevail: the dream hallucinates, it dramatizes an idea, giving us the impression of experiencing a thought in which we blindly believe. Dreams are the suspension of the authority of the I/self; it elapses without reflection or reason. Immoral dreams prove that the dreamer knows the content but not the psychic impulse that led to the dream. Freud refines his discovery, stating that a dream fulfills a disguised wish.

INTERPRETATION AND PSYCHOLOGY OF DREAM PROCESSES

The basis for the interpretation of dreams is how the dreamer verbally reports the manifest content of the dream. Since people often forget dreams or tend to reproduce them unfaithfully, the sooner the documenting of the dream after awakening, the more trustworthy it will be. Freud states that the little details in a dream offer the possibility of a complete interpretation and that how someone narrates their dream is just as important, if not more, than the content of the dream.

A doubt in narrating a dream is what interests the most for analysis because it is already the effect of resistance. While telling the dream, the word choice reveals relationships between the manifest content and other words/ideas leading into latent content – via linguistic association (see image below). One can never be entirely sure the interpretation is complete, even when it apparently has no gaps.

Awakening takes time, and the dream happens during this time. It is not the dream that awakens us, but rather the awakening that makes us remember the dream – Freud

The lay world has always searched for ways to interpret dreams, ultimately comprising two views. One considered a symbolic method would substitute the content of dreams for an analogous version. A second method, cryptographic, sees every aspect of the dream as a secret code; each sign is translated according to a key from a book of codes. Although in The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud leans quite heavily in assigning meaning to dreams as one would find in a manual, he gradually gravitates toward the idea that interpreting a dream is not the analyst's work but the patient's. As such, the meaning of a dream shouldn't follow a manual but be subjective to the dreamer. According to Freud, if the dream is a symptom, it should be treated as such.

Treating a symptom then would require setting up the patient for the work of interpretation of their dreams. If Freud learned of the importance of letting patients speak their minds when treating hysterical symptoms, here he sets a foundational principle for Psychoanalysis: free association. The intent here was to simulate a state of falling asleep (or hypnotic) to allow visual and acoustic images to appear, turning off the automatic censorship that filters thoughts. The dreamer should everything that comes to mind, assuming a neutral posture, and observe, not reflect, on what's being said. A process of self-discovery. The goal was to dismember parts of the dream, allowing the work of free association to find out to what wish the dream responds.

A PERSONAL TAKE

Controversial, misunderstood, outdated. I’ve seen many unfavorable or reluctant opinions about Freud’s work and the role of dreams, in particular. I can assert, however, that in reading The Interpretation of Dreams, one will find sound theoretical research and extremely compelling arguments that tackle the mysteries of not only why and how dreams are formed but mostly why so often we tend to neglect or at most pay little attention to them. I like to compare Freud’s views on dreams and Psychoanalysis as a practice with the system of democracy: easy to criticize and difficult to find a better one.

It is difficult to disassociate Freud from The Interpretation of Dreams and dream interpretation from Psychoanalysis. Arguably, the birth of the praxis happens with the launch of this book in 1900. Freud had long worked on it before its release, and he foresaw the divisive potency of the theory he was about to launch and how it related to the unconscious. Typical of a paradigm shift, it took years to assimilate the role of dreams in accessing the unconscious and adopt dream interpretation in clinical practice. Freud was aware of this, and in each of the book’s following editions, he made sure to acknowledge not only the difficulty pushing the theory but how it ultimately became accepted by ever larger groups. It’s fair to say that, from The Interpretation of Dreams onwards, Freud no longer saw himself as a neurologist but as a psychoanalyst. Gradually, his discoveries moved him away from the traditional medical circles as he expanded his influence over a newly formed field of psychoanalysts that slowly began to adhere to his views.

While reading this book, it helps to remember the context of the time it was written (and how disruptive some of his ideas were – and still are – at the time) and that this is still a theory: open for debate, and gladly so. Like all of Freud’s work, The Interpretation of Dreams is an iterative piece of constant testing and formulating hypotheses. Several times he revised or updated his previous assumptions and produced new knowledge, in a genuine scientific inquiry.

With care,

Gui