J’appele un chat de un chat (I call a cat a cat). – Freud

INTRODUCTION

One of the “Big Five” cases of Freud, Dora was the first relevant clinic case he documented, which took place during his writing of The Interpretation of Dreams and Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality. We find a Freud trying to validate his thesis about the neurotic hysteria – comprising of a sexual etiology, a psychic conflict, and syphilitic inheritance – as well as demonstrate how the psychoanalytic, supported by dream interpretation and free association, dispositioned itself from catharsis and hypnosis.

Apart from the fact that the case did not necessarily end well, Freud is as candid about this fact and states from the get-go the difficulties in establishing transference with a young 18-year-old virgin in Dora (whose real name was Ida Bauer) suffering from sexual repression so typical of an era of wide-open neglect for women’s rights (let alone their desires). The attentive reader will notice how Freud’s management of the transference was rather crude at this point in his career.

It is worth noting that, at the time, it was just as inadequate for a doctor to address the topic of sex with a female patient as it was immoral for the patient to disclose it in such a setting. However, because of the broad number of women showing severe signs of neurosis associated with extreme unhappiness from being confined to torturous married lives, Freud understood the need to address the elephant in the room. Even so, he took extra care by opening the case announcing that his approach had to be as impartial and direct as the situation required it to be. If sex was the theme behind the symptoms, then sex should be the subject reckoned with.

This radical approach, way ahead of his time, often required Freud to educate his patients on the sexual world by explaining sexual phenomena and naming the sexual organs if they were unknown or unspoken about, by calling them by their technical name. J’appele un chat de un chat – “I call a cat a cat.” said Freud.

Concepts covered or cited in this text: neurosis, hysteria, phobia, and obsession; dream interpretation and free association; conscious insincerity, unconscious insincerity and paramnesia; memories and fantasies; psychic barriers, self-reproach, and hysterical symptom.

PREFACE

The text opens with a preface where Freud shares some of his notes about the treatment and sets the expectations about how far the study of one case could go. He circumscribes the goal of the treatment, from the standpoint of a developing psychoanalysis, in determining the hysterical symptoms and establishing the structure of neurosis. The approach had switched from a traditionally medical one tackling the patient’s symptoms to a pioneering psychoanalytical one, letting the patient speak through free association and produce fragmented material (pertaining to various periods and contexts of the patient’s history yet connected to the solution for the symptom presented) allowing this emergence to confer the direction of the treatment.

Freud acknowledges what he named three incompletenesses of this case:

It was about an archeological study of the patient – without a pre-plan, and the doctor can only discover so much.

The writing focuses on the case’s results and not the process that led to Freud’s interpretations, already introduced elsewhere in his work.

One case only will never suffice to explain the whole of hysteria.

Lastly, he declares that a doctor makes two commitments, one to the patient and another to science, justifying why he decided to publish Dora’s case four years after her treatment, which could still pose a risk to the patient’s identity.

The dream is one of the detours to circumvent repression, a means of indirect representation from the psyche. – Freud

PATIENT’S CONTEXT

Ida Bauer (nicknamed Dora) was, at the time of her treatment with Freud, an 18-year-old daughter of a wealthy Austrian industrialist, Phillip Bauer, a man Ida admired. The father, who had suffered from health issues related to syphilis and was treated for that by Freud, had an affair with a woman, under the nickname Mrs. K, who took care of him in the most severe moments of his illness. Mrs. K was married to Mr. K, and the couple lived in Merano, in the Tyrol region, where Phillip would go in critical moments of his illness.

Aware of the affair between his wife and Phillip Bauer, Mr. K is initially displeased but later tolerant of it; he tries first to seduce the Bauers’ housekeeper before turning his focus to the young Ida in a drama that climaxes with a scene taking place at Lake Garda, where she slapped him on the face after he attempts to kiss her.

Ida’s mother, Katharina Bauer, was of modest background and spent most of her time in house chores. She suffered from what Freud named “domestic psychosis.” Her relationship with Ida was nil, and it was the housekeeper, considered “liberal and liberated,” who was responsible for educating Ida. It was through her that Ida would learn about adult life. The Bauer couple also had another child, Ida’s brother Otto, whose main desire was to free himself from family fights. He would occasionally argue with his father – whose adulterous relationship he did not disapprove – and often side with his mother, in an evident Oedipean dynamic noticed by Freud: the son and the mother, and the daughter and the father.

After the scene at the lake, Ida tells her father about the incident in hopes of unmasking Mr. K, only to find the two men accusing her of lying after the vehement denial from Mr. K. Ida, who had already had troubling symptoms in childhood, is affected by severe neurotic disturbs, including a convulsive cough, aphonia, depression, and suicidal tendencies. Her father takes her to see Freud for an agreed short treatment, where he briefed Freud to bring his daughter back to her senses. Little did he know that Freud had his own agenda.

CLINICAL CONTEXT

At this point in his career and in the development of psychoanalysis, Freud already had enough knowledge about the functioning of a neurotic structure, as displayed in the number of patients he oversaw. Hence why, similar to providing a context for the patient in question, Dora, Freud also chooses to describe some clinical phenomena that, despite each patient’s singularity, were standard to a certain extent.

A typical trait was the inability to narrate one’s own story in a clear and organized manner, characteristic of neurosis, often manifested in the three forms as follows:

A shyness or modesty: when the patient remains silent about a part of what they know and should tell – an example of conscious insincerity.

A part of knowledge excluded from the patient’s account (amnesic) – is an example of unconscious insincerity.

True amnesias, both of old and recent memories, are in a stage of repression clouded by doubts or misconceptions and often forgotten – leading to the formation of paramnesias.

The state of memories is a necessary correlate of the symptoms of the illness: the worse one narrates or remembers, the more acute the symptoms are. – Freud

The theoretical goal is to heal the damage to the patient’s memory, while the practical goal is the removal of symptoms and their replacement with conscious thoughts. On the same token, Freud reinforces that, in terms of the treatment, the patient’s dreams represent one of the pathways to access the psychic material that, due to the aversion it provokes, has been blocked from consciousness and repressed, becoming pathogenic. He says that, at the end of the treatment, the patient is able to narrate their story in a clear and organized manner.

THE TREATMENT

Freud made use of his method revolving around dream interpretation and free association, particular to psychoanalysis. However, he was still grasping to position himself as a psychoanalyst. In sessions, he learns about the drama surrounding Dora, that she had been aware of her father’s adultery for months, rejected successive seductive approaches by Mr. K (ultimately leading to the slap on the face scene), and that was taken as a liar by both men. Furthermore, Mrs. K accused her of being into “pornographic books,” when in reality, those were sexology books gifted by Mrs. K herself. Dora’s father, Phillip Bauer, expected that Freud would end his daughter’s sexual fantasies.

The treatment, while short, was intense and decisive. It centered around the detailed interpretation of two dreams that Ida (Dora) recounted. The first dream, the one where Ida’s house is on fire, and her father saves her while leaving her mother behind, reveals, among many things, the fact that Ida had already introduced herself in sexual life (via masturbation) and that Mr. K., in fact, enamored her. Her unconscious repression led her to ask her father for protection from this attraction.

The second dream, about the death of Ida’s father, is where Freud gained insights into Ida’s broad knowledge of adult sexual life. However, in a clear case of yet unskillfully managing the transference, Freud prematurely exposes Ida’s desire and induces her to confess her attraction for Mr. K, which she denies, leading her to interrupt the treatment after three months. Having realized that Freud did not side with him, Ida’s father eventually loses interest in his daughter’s treatment. A few years later, Freud would add that he was not able then to establish a homosexual link between Ida and Mrs. K – a point of view that rendered Freud challenged by some of his peers.

What is known outside of Freud’s text is that, although Ida never cured herself, her symptoms eased from time to time. She later married a man who used to work at her father’s factory, with whom she had a child. Later, having emigrated to the United States, she eventually confided to another industrialist, Felix Deutsch, confessing the story of her treatment. Deutsch quickly realized that Ida was, in fact, Dora, who had already been made known after Freud publicized the case. According to Deutsch, she was proud to learn that her case had become symbolic in the psychiatric literature, and when recounting how Freud had interpreted her dreams, her symptoms disappeared shortly after.

Ida eventually passed away, in New York, from colon cancer, a product of her historical untreated intestinal constipation which metaphorically represented a move against her mother’s obsession (cleaning) manifested in Ida’s inability to “clean her intestine” – a take offered by Freud’s lifelong friend and colleague, welch psychoanalyst Ernest Jones.

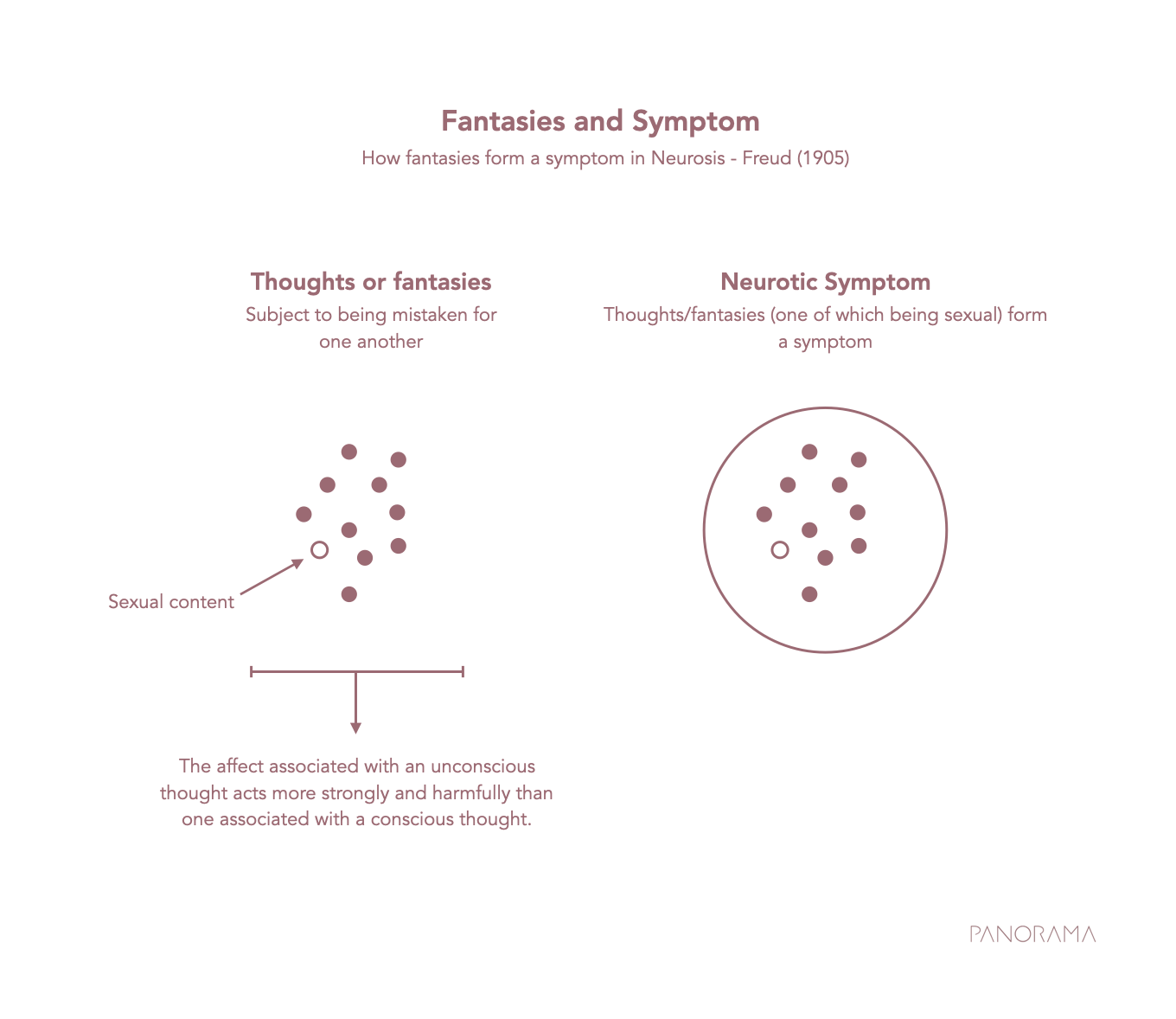

ON THE HYSTERICAL SYMPTOM

The main takeaway from the treatment was Freud’s validation that hysteria has a strong correlation with the psycho-sexual life of individuals and their repressed desire. However, the trauma leading up to the symptom does not determine it – each situation is unique. In Dora, some symptoms had already been present since her infancy, which denotes the possibility of an inversion of an affect, meaning that when something that is experienced as pleasurable can turn into displeasure by psychic barriers of self-reproach. Moreover, there can be a displacement of sensations, such as a genital sensation that migrates and manifests in a different body part. The hysterical symptom is about the psychic and somatic combined, and it repeats itself when a sense is attributed to it in accordance with repressed thoughts/experiences/sensations.

To a certain point, every neurosis presents very similar psychic events and processes, and only then does the typical somatic compliance of hysteria come into play - where each case manifests in a different body part - or a phobia or obsessive idea - both psychic symptoms. – Freud

The illness in hysteria represents a psychic solution where the individual gains something from it. The possibility of curing a neurotic symptom is linked to discovering the purposes (utilities) of such symptoms: whether they are internal motives (self-punishment, regret) or external motives (obtaining something from someone or distancing someone from someone else). The symptom can change its meaning, even its most significant, over the years. In neurosis, symptoms can persist even if the thought expressed in them has lost sense.

A PERSONAL TAKE

Whether Freud’s obsession with validating his theory led him to see what he wanted to see instead of letting the case emerge new possibilities that could divert from his pre-established views is perhaps a subject for a future text here. Nevertheless, the insights he obtained from such an abbreviated treatment were outstanding, and again we can find Freud at times humbled by what he did not know.

At a time when he found himself amid heavy skepticism, above all from his German counterparts, who not only straight up denied the existence of hysteria as a medical illness, but that they were only present in female patients and they all faked them, Freud managed to push the envelope and go against the common practice to reconstruct the unconscious truth in Dora, delivering foundational insights about hysterical symptoms and the structure of neurosis.

With care,

Gui